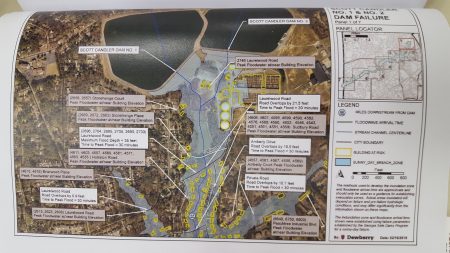

If the dams at DeKalb County’s twin reservoirs in Dunwoody failed, a roughly 10-foot wall of water would slam into nearby houses. Within an hour, the flood would lap against I-285 at a depth of 10 to 12 feet, and flow nearly five miles down the Nancy Creek’s bed in Brookhaven. Some areas would be submerged in more than 40 feet of water.

Hundreds of residents in the flood path would have little warning. Yet they would still have a precious chance to flee, because DeKalb recently filed an “Emergency Action Plan,” or EAP, about where the water would go in a worst-case scenario and who would get the alarm.

But among the 11 state-monitored public and private dams in Reporter Newspapers communities, that’s one of only a few that filed EAPs by a July 1 legal deadline. The state Safe Dams Program is working to get the others — and all of the roughly 500 “high-hazard” dams statewide — to get into compliance.

“You’re realizing the sad reality” of how fast a dam-failure flood could hit homes and roads, said Tom Woosley, head of the Safe Dams Program, as he displayed the “inundation maps” for those Scott Candler Reservoirs in DeKalb. “I’ve had some owners go, ‘I didn’t know my dam could impact so much.’”

The state’s classification of a dam as “high-hazard” is not a judgment about its condition; the Candler Reservoirs, for example, have received recent good inspection reports. “High-hazard” means that if the dam did fail for whatever reason — accident, natural disaster, structural failure, terrorism — the flood likely would kill people downstream.

The lethal potential of water was fresh on Woosley’s mind. As he was displaying various EAPs in a state records office in downtown Atlanta, where they are available only as printed documents, the city of Houston was drowning in historic flooding from Hurricane Harvey.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency produced the concept of the EAP for public safety. The format varies state to state, but the basics are the same. There’s a map detailing the area that would be flooded in a worst-case, “sudden failure,” meaning all the water coming out of the dam within six minutes from the spot where the water would flow the strongest. There’s a list of all properties that would be flooded.

For dams where a flood would affect only a small number of homes or other buildings, the EAP may include contact information for specific people there. For dams with bigger impact zones, there is simply a list of properties that authorities would alert by making a reverse 911 call to all numbers in that area. For DeKalb’s Candler Reservoirs, that list of properties is nine pages long.

EAPs are intended for use by both dam owners and local governments. For the owners, the EAP notes three levels of problems and required responses.

Level 1 is an unusual wet spot appearing on the dam, which only requires “monitoring.” This level is intended partly to encourage dam owners to make regular inspections.

“All dams leak,” Woosley said, so the important part is knowing when a leak is unusual and a sign of a structural problem. “Part of the idea is the owner … should be inspecting this dam routinely … There’s some judgment in there, which goes back to, ‘Hey, owners. Get to know your dam.’”

The other two levels are for serious problems and both require immediate notification of people in flood-zone properties. Level 2 is when water is seen flowing through the dam, requiring “protective actions” and repairs. Level 3 is imminent failure, which requires evacuation of everyone in the flood zone.

Local dams and EAPs

The Safe Dams Program has a small staff that often struggles to find owners and receive regular inspections of high-hazard dams, especially the many little-known private dams that impound leisure lakes in subdivisions. It’s having similar challenges on the newly required EAPs.

Woosley said the state received “one that said, ‘In the event of failure, we’ll run for it.’” That was the entire EAP filed for a privately owned dam in Cobb County. “They have since reconsidered their philosophy,” he added.

Of 11 local high-hazard dams, Woosley said, only three have completed EAPs: the Candler Reservoirs (including separate flood maps for each reservoir); Brookhaven’s Murphy Candler Lake; and Lake Northridge in Sandy Springs.

Those he said have not submitted include: Capital City Country Club Lake in Buckhead; Silver Lake in Brookhaven; Dunwoody Club Crossing Lake in Dunwoody; Lake Forrest on the Buckhead/Sandy Springs border; and Cherokee Country Club Lake, Peppertree Lake, Powers Lake and Tera Lake in Sandy Springs. Some owners have said they’re working on the EAPs, Woosley said, and the owners of Dunwoody Club Crossing Lake are appealing their high-hazard classification.

Safe Dams does not monitor federally regulated dams that may also be high-hazard. One of those is Morgan Falls Dam on the Chattahoochee River on the Sandy Springs/Cobb County line. However, such dams also file EAPs with the state; the latest Morgan Falls plan was filed in January.

Lake Forrest is among the many high-hazard dams with complicated ownership and repair issues. It sits directly on the Atlanta/Sandy Springs border beneath Lake Forrest Drive, and has a homeowners association involved in ownership as well. The city of Sandy Springs is taking the lead on managing state-ordered inspections of its condition and consideration of possible alternative designs, but the process has dragged on for years.

Meanwhile, the lake has been drained, though large storms could fill it up rapidly, the state says.

Sandy Springs city spokesperson Sharon Kraun said Safe Dams granted a two-month extension on filing the EAP while alternatives are finalized as a necessary step to creating the response plan.

But Woosley said that’s not quite true. “We can’t grant an extension … we can grant some discretion on enforcement,” he said, referring to the possibility of the state Attorney General suing the owners. “But technically, any that didn’t make the July 1 deadline, they’re out of compliance.”

With Lake Forrest, Woosley said, the city’s decision on a long-term fix is “irrelevant” to filing an EAP because the flooding issue would be similar. “You can get something in,” he said.

A major issue addressed by EAPs is that people often don’t know they live downstream from a dam. Woosley said people should check a program like Google Maps to see if they live along a waterway or valley that is near a dam — and any lake or pond in this area has a dam, he said.

“On the flipside, don’t panic,” if you’re near one of these high-hazard dams, he added. “Having an EAP is not a bad thing … and having an EAP does not mean the dam is going to fail.”

Woosley said that homeowners are sometimes concerned that their property value could decrease due to its listing on an EAP. “I have no evidence that has ever happened,” he said.

Editor’s note: This is one of a series of articles about dams in our communities. Previous installments have looked at the location and condition of the 11 local “high-hazard” dams; the cost of maintaining these dams and the long process of repairing them; concerns about the lack of emergency plans in case of a dam failure; and how the state inspects the structures.