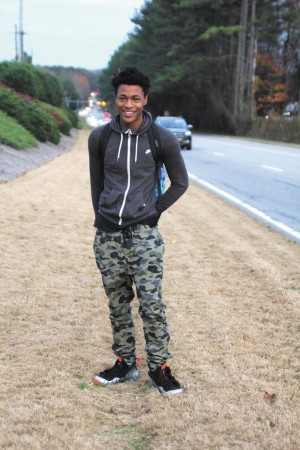

Dunwoody resident Rashaud Stockdale walks to work on Cotillion Drive in a rut worn in the roadside grass. The road is a major connector to I-285 and the Georgetown commercial district, but for pedestrians, it’s like rural pastureland.

“I’d say it feels dangerous,” Stockdale says of the off-road hike he sometimes has to make in the dark.

Meanwhile, in Sandy Springs, Cedron Tigner escorts his visually impaired relative Hershell Horton along Hammond Drive. Instead of a sidewalk, there’s a muddy trail, studded with exposed tree roots and stones, which looks imported from a backwoods park. “Taking a chance every time,” Horton says of his walk to a convenience store.

These trails blazed by pedestrians are known as “desire paths” or “desire lines”—or, more picturesquely, “goat trails.” For decades, Atlanta’s car-centric suburbs left pedestrians to fend for themselves. But that’s changing.

Sidewalks are now replacing desire paths on such routes as Buford Highway in Atlanta and Brookhaven. But finding the money can be tough, and public accessibility can still spark debates over keeping desire paths in such places as Buckhead’s Atlanta Memorial Park.

Desire paths are “especially common in areas where people have no choice except to walk or use public transit” because they don’t own cars, said Sally Flocks, president and CEO of the Atlanta-based pedestrian advocacy group PEDS.

“I think attitudes nationwide are changing. I do think a lot more people want the sidewalks,” Flocks said.

But there’s a big backlog to catch up with. DeKalb and Fulton counties began requiring new developments to include sidewalks in the 1990s, she said, and Atlanta and the Perimeter’s newer cities do as well. Linking those disconnected bits of sidewalk is expensive.

“Probably the most important [challenge] is money,” Flocks said.

That’s true in Dunwoody, where the city plans to replace part of the Cotillion Drive trail with a paved multi-use path in 2017.

The new multi-use path is coming because the city is aware of Cotillion’s obvious pedestrian problem, said Public Works Director Michael Smith. But it’s taking years because new sidewalks cost roughly $250,000 per mile—Cotillion’s multi-use path probably will cost more than $1 million. The city’s overall plan for 20 miles of new sidewalks will cost at least $5 million—or about 16 percent of the city’s $32 million annual budget, if it were all done at once.

“It’s not something that can all be done at one time,” Smith said. “We’re trying to chip away a little bit each year.”

Cotillion, running a mile along Dunwoody’s southern border between North Peachtree and Chamblee-Dunwoody roads, is a classic environment for desire paths.

Smith said it likely was built as part of I-285’s construction in the 1960s or ’70s, when pedestrian structures weren’t automatically included and the area was less developed. Since then, two multifamily housing projects have added disconnected pieces of sidewalk. Even the desire path disappears at the Georgetown end among busy parking lots for gas stations and fast-food restaurants.

Jamie Lee lives on one of Cotillion’s sidewalk islands, the Madison Square at Dunwoody condos. She walks for health, but cuts through the parking lots of a nearby office park to avoid the desire path, which she doesn’t find so desirable. “It’s not as safe because it’s not flat,” she said. “And traffic is so bad here.”

Pedestrian safety drove the Georgia Department of Transportation to upgrade walkways along Buford Highway, a state route, starting in 2012. Buford was lined with narrow desire paths along the high-speed, multi-lane road. And it was infamous for pedestrians killed by cars—at least 22 between 2000 and 2009, according to a report in Creative Loafing.

GDOT’s recently finished $11.5 million project targeted the Buford corridor from Lenox Road in Buckhead to just south of Clairmont Road in Brookhaven. It replaced desire paths with sidewalks and installed medians and signalized crosswalks. With another round of funding, GDOT plans to extend the improvements north from Clairmont Road into Chamblee, said spokeswoman Annalysce Baker. But that’s not until 2020, so rough desire paths remain in use there.

Flocks said the method of getting sidewalk funds can be an issue, too. PEDS opposes metro Atlanta’s tradition of treating sidewalks as something for private property owners to install and maintain, calling that unfair and inefficient. “We’ve said [sidewalks] should be paid for with public funds because it’s a public good,” she said.

The burden on private owners can trigger resistance from those who may “want [their land] to have a rural feel. They don’t want people walking in front of their property,” she said.

Those issues can spark debate even on public land, such as a current proposal to add sidewalks, as well as paved interior paths, at Atlanta Memorial Park. At a recent community meeting, advocates said paving the existing desire paths along Woodward Way and Wesley Drive is a basic safety and accessibility matter. Opponents worried that sidewalks could damage the environment and attract overuse of the park.

All of those issues come together at Sandy Springs’ Hammond Drive. In its first decade of existence, the city has installed 20 miles of sidewalks. But Hammond remains an obvious sticking point, lined with a ragged desire path despite linking the increasingly walkable Perimeter Center and Roswell Road downtown district.

The main reason is strong local opposition to the city’s plan to widen Hammond, which would include adding sidewalks. The widening project still lacks full funding, said city spokeswoman Sharon Kraun.

Adding sidewalks to the existing road isn’t in the near future, either. “Proof of pedestrian activity such as desire paths” is one criterion for prioritizing new sidewalks, Kraun said, but added, “In our current list of sidewalks scoring, Hammond is not on that list.”

With cities now working under sidewalk expansion policies, paving the old desire paths is probably a matter of when, not if. But patience can be hard for today’s walkers like Stockdale, who sometimes arrives at work with soaked shoes from wet grass and hikes home on the road’s white line because it’s all he can see in the dark.

“Hey, make ’em put a sidewalk out here for me!” he called as he trudged home down the Cotillion Drive path.