Cinematographer Roger Deakins and his collaborator and wife James Deakins are headed to The Plaza and Tara Theatres for a three-night extravaganza in early December.

Roger Deakins is best known for his frequent collaborations with Ethan and Joel Coen, Sam Mendes and Denis Villeneuve, but has a career that spans over decades working with multiple directors. He is the recipient of 16 Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography, winning two for “Blade Runner: 2049” and “1917.”

James began her career in the industry as a film lab technician at DuArt Film Laboratories and then a script supervisor in production. After she and Roger met, she eventually moved into the role of a full time creative partner with Roger. The two work on their approach to each film together, with James overseeing aspects such as communication with various departments and coordination of details on set while Roger focuses on capturing the visuals.

The duo’s partnership has evolved into the creation of a podcast, Team Deakins, where they interview various industry professionals about their specific processes. In 2021, Roger released a book called “Byways” to celebrate one of his favorite hobbies, photography. The book is a collection of black and white still photographs of everything from life in rural North Devon, to photos taken while on location filming “Skyfall” in Scotland.

During the couple’s appearances in Atlanta, they will attend a book signing at A Cappella Books on Dec. 5 from 3:30-5 p.m. They will also sit for Q&As before three screenings: “The Man Who Wasn’t There” on Dec. 5 at 7 p.m. at the Plaza, “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” on Dec. 6 at 7 p.m. at the Plaza, and “Prisoners” on Dec. 7 at the Tara. Pre-signed books will be available at screenings, but the only way to get the booked signed in person is to go to A Cappella on Dec. 5. Tickets can be purchased to the screenings online.

Prior to the screenings, Rough Draft Atlanta spoke with Roger and James about photography, filmmaking, and working together. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

In the foreword of “Byways,” Roger, you said that photography played a role in your development as a documentary filmmaker. I wondered if we could just start there, and you could elaborate on how that helped you develop?

Roger Deakins: Well, it was just a sort of progression. I went to art college, and I enjoyed painting. My painting was quite naturalistic, I suppose, so in art college, I discovered photography was probably something more suitable for me. It just developed from there. I was at art college, and a friend of mine talked about the National Film School, which was opening outside of London for the first time … I didn’t get in the first time I applied. I worked as a photographer for a while at an arts center, which was a wonderful opportunity for me. And then I applied to the film school the next year and got in. That was just my slow development in how I was very lucky to find filmmaking, actually, and get a sort of entry into it through film school.

In the foreword you also talk about how film is a very collaborative process, and photography is something that’s a bit more personal, which makes a lot of sense. I wondered if you could talk about how else those two mediums sort of differ for you artistically and creatively?

Roger: I’m a cinematographer. I’ve spent my life working on movies, but photography is a hobby, really. You know, it’s like a relaxation from working on a movie, because on a movie, you’ve got so many people around you and so much – that stress level is so high, you know, the pressure of making a schedule and …

James Deakins: Making everybody happy.

Roger: …Pleasing the actors, and a director, and everybody else, and running a crew as well. It’s kind of stressful, so I kind of love still photography because it’s just me and the camera, and I can make a decision of what I want to take a photograph of and exactly where I’m going to do it, you know? I find it a great relaxation from working on movies, really.

Speaking about that collaboration aspect – you two have been collaborating together for years on numerous projects, which include a podcast called “Team Deakins.” I read part of the impetus for that was you do a lot of Q&As, and you get asked a lot of the same questions – as I’m sure I’m doing now. I wanted to ask, how has the podcast evolved from that original idea, and how has your partnership evolved as well?

James: It’s evolved a lot from the original idea. Originally it was just answering specific questions, but then we started talking to other people that we knew and it got more about filmmaking, and how it’s such a collaborative process, and everybody – they may be having the same role, but they approach it in their own way. Then we talked to people we didn’t know, and it just kind of evolved.

Roger: Originally, it was a sort of branch, we felt – a branch of a website that James had started up years ago, you know, just to answer students’ questions. So we started a podcast, or James did, and we did a few [episodes] that we were thinking was just going to be with the immediate crew that we work with and people we know. And it’s just kind of steamrolled from there, really. It’s now becoming unstoppable [laughs].

James: It’s funny, because it’s not just for students. People in business, a lot of them, they listen every week. Someone told me the other day that when they accept a job, and they find out who’s on the job, if they don’t know some people, they’ll go to the podcast list and see if we’ve talked with them. They’ll sort of know them before getting onto it, which is kind of nice.

Roger: It’s been great for us because … we’ve talked to people we’ve never met, you know? It’s just fascinating, us asking them about their process – different directors, and different cinematographers, whatever.

One thing I like about it is it’s not just directors, or cinematographers, or actors. You guys have costume designers, producers, all kinds of people in the industry, which is nice to see.

Roger: That’s really important, because film is a collaboration between many, many different departments. I think there’s a little bit of a misunderstanding about that, how much of a collaboration it is.

James: I think, also, it’s interesting to people to know how much the prop person does. You know? They never stop to think about it. It’s not that they didn’t think they did something. One producer, who has been on and is a big producer, he said he loved hearing more about the different departments, because although he knew the departments – he’s a big producer, he knows all that stuff – he never gets a chance to sit down with them and say, well why do you do it this way? So he was learning too.

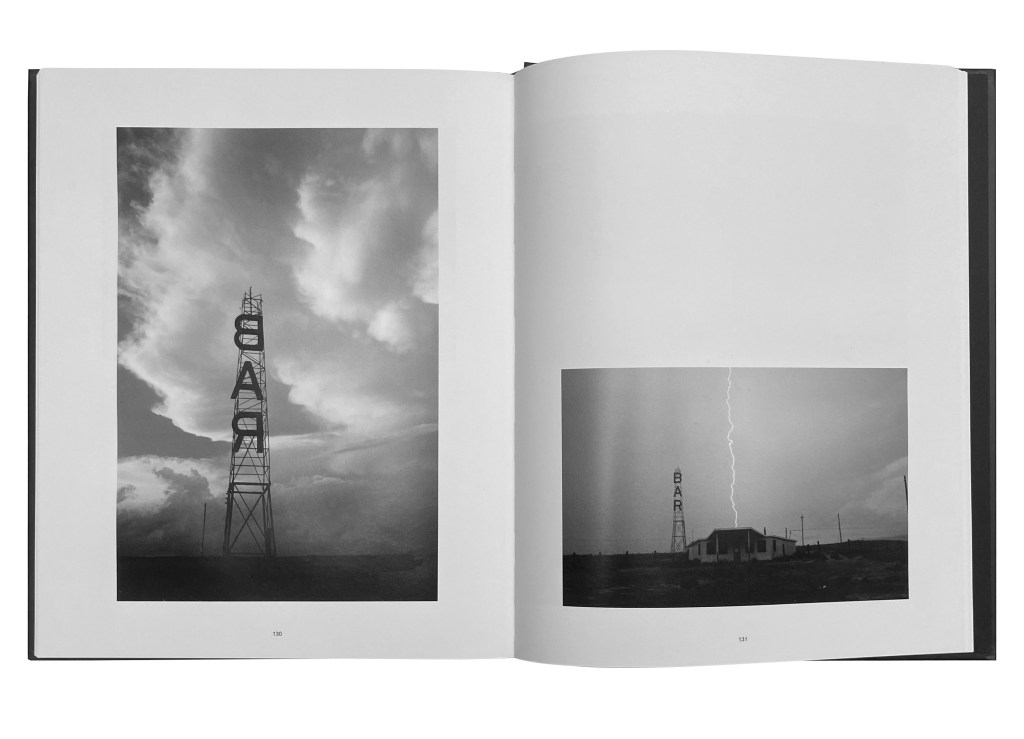

Speaking about process, it’s very interesting to read about the process of taking these photos. A lot of it seemed like you were just walking around waiting for inspiration to strike. But there are a few photos – for instance, the one with the lightning strike – where I read that you went out there a few times hoping for the weather to be just right. But even then, the strike had to come down a certain way to get that picture. To me, that seems like an interesting combination of intention and luck. How much of those things do you see in photography or filmmaking?

Roger: I just love exploring different places anyway, so to do it with a camera – I mean, often I just go somewhere and wander around a town that I’ve never been to or something, and never take a photograph. But then sometimes, I latch on to something that I find amusing or a little something that I feel is worth a photograph. In the case of the one with the bolt of lightning hitting the bar, I’d been wandering around, and I saw that location and I thought – yeah, it’s an interesting shot, but what if there was a thunderstorm, or there was lightning behind the bar? So I had something in mind, but it’s serendipity that it was one bolt of lightning, and it was just that one steak coming right down the middle of frame.

I don’t know how much input you had into this, but I love the picture on the cover, with the hands out the window. How was that shot selected to be the first thing that we see?

Roger: Well, we were talking with the publisher, weren’t we? We were saying … You know, there’s a number of photographs from the English seaside and stuff, and we thought about one of them. But then [we] didn’t want to be too specific, so the shot of the hands …

James: It’s kind of a one-off one.

Roger: …It’s a one-off, and it’s very graphic, and in its own way it’s quite moving as a shot. It seemed to encompass a lot of the other ideas in other photographs.

James, something you said in an interview stuck out to me, that when you both see the first cut of a movie, it’s always sort of disappointing because you only think of where you had to compromise, or the shots you couldn’t get. How long does it take you to get past that initial feeling of disappointment?

James: Five years, or something?

Roger: At minimum [laughs].

James: It’s very funny, it’s very odd. We’ll just randomly maybe see a film that we did on television – five years down the road or something, we’ll see a piece of it – and we’ll go, huh. That’s not so bad! You know? But it’s just that you really do get so caught up in what you didn’t do when you first see it.

Roger: I mean, I think everything you do on a movie is a compromise, because you’ve only got so much time and so much money and you’re restricted or whatever by the conditions of where you’re shooting and a lot of other things. So you always have those compromises in mind when you’re watching something. I do, anyway. It takes a while to sort of realize, well – it wasn’t so bad after all [laughs].

All of these photographs are in black and white, in the book. I was reading another interview where you described that choice as “striving for simplicity.” Obviously, you don’t always shoot films in black and white, but I wondered if that concept also carries over for you when you’re shooting films?

Roger: Yeah, very much. I think the danger with color, it can just be kind of like eye candy, you know? It’s not actually serving the story or anything. I mean, why I like black and white in photography, I suppose it’s that’s what I grew up with, admiring the photographers of the time when I was a teenager. Everybody was shooting black and white, you know, until William Eggleston, people like that, started to understand color, really, and how you could use it. Most people were shooting in black and white. That’s probably still true today, you know? Most photographers that are highly renowned and respected, I suppose most of them shoot in black or white. But yeah, I love the simplicity of the image. I love it because it’s about the composition, and it’s about the juxtaposition of images within that frame. That does relate to the way I see photography in movies. I think you sort of strip it down to its basics, really. Especially as a shot doesn’t last very long on a movie screen, you know? And if it’s too complex, the audience isn’t getting the information you’re trying to put across.

I was reading another interview with you both, and there were a couple of things you both said about visual effects and those progressions that were interesting to me, starting with the fact that something like “1917” was more visual effects light comparatively to what people might think, and something like “Empire of Light” actually probably has more than you might think. In that same interview, I read that you guys try to put consulting on visual effects into your contracts, which isn’t necessarily normal. How have advancements in visual effects changed across your careers and how have they changed how you work?

James: For one thing, there’s a lot of requirements of what visual effects need, the kind of elements that they need, and stuff – things that we have to think about, or we have to do a clean pass each time.

Roger: But I think more fundamentally, you know, visual effects can seemingly do anything now. But does that make it a reason to use visual effects?

James: Yeah, should you.

Roger: The reason for using visual effects is important. I think what we were saying about the difference between what you think of “1917” and “Empire” – I mean, the visual effects in “Empire” is like, we’re in a seaside town shooting 1980, but you can’t really change everything that’s been modernized since 1980. So there’s a lot of little visual effects that are done, but nothing really that’s altering, in a fundamental way, what the frame is … But on “1917,” we definitely tried to do as much in camera as possible. So a lot of the explosions that you would think would be CGI these days were not. They were actually live. I like to do as much in camera as possible, personally. But obviously, certain things you can’t, you know? You can’t, these days, afford a huge crowd of extras for one or two shots.

James: It does make a difference, I think, to the actors as well, as well as everybody else creating that particular scene. When we did “Blade Runner [2049],” there are less visual effects in that than you would think, because we built the close and the mid range. It’s just in the background that we made the changes. But that’s really important for the actor, to actually be in that world.

Yeah, I would think that would matter to everyone, just to have something physical to look at and react off of.

Roger: Also there’s this sort of thing about the work going down the line in post. You know, if you don’t have the foundation of the shot, then there’s no reference for those artists to work with and build on. The trick about, I think, cinematography, or the visualization of a story in a film is the constituency of the viewpoint, or the consistency of the look of the movie from scene to scene. And when you’re doing a lot of visual effects, they get farmed out to different companies, different people, different people with different ideas. So suddenly, you can get a bit of a mess of visual ideas coming in. I think it’s the role of the cinematographer to keep the identity on the same plane.

Jumping back toward the book. I wanted to talk about how the photos are structured throughout. I was looking through the index, because I wondered if it was chronologically – kind of loosely, but not really. I think one of my favorite pairings is on page 148 and 149, two statues of Winston Churchill and Józef Piłsudski. I recognized Churchill, but I had to look up Piłsudski, and obviously that colored the way I looked at them together. Could you talk about how the photos were structured and how you put them together?

James: Layout was important. We went back and forth a couple of times.

Roger: Yeah, we went back and forth quite a bit. I mean, I think the earlier ones are the earlier ones, you know? There’s a lot from Devon when I was actually working as a photographer. And then there’s a lot from the English seaside that I’ve taken over the years, so they come from all different moments in my life.

James: You know it’s funny, because we’re doing some exhibitions of the prints, and in doing those, we get the opportunity each time to sort of switch it around. We are doing these different combinations, because we know the book so well at this point, but it’s kind of fun – oh, well let’s have this character facing this character on this row …

Roger: It’s like composing an image for a movie, or a photograph. It’s the same thing. It’s how do you put two images together, and they become something else? It’s kind of interesting, laying out some of these exhibitions. Especially because there are quite a few photographs that aren’t in the book as well. So, you know, it’s been really interesting.

James: Also in the book, the ones that would go two pages versus one page was a discussion.

Roger: Some of them, like these photographs from an “Around the World” yacht race I was one. That’s just photographs there because they’re part of me, so I put them in as a sort of little illustration of my life, I suppose. It’s very personal. It’s not really meant to be much more than my sketchbook.

It’s interesting that you’ve gotten to play around with them. Can you remember which ones you changed?

James: We did a couple of times, and also some things went in and out.

Roger: Yeah there’s quite a few. You know, I still go back and forth with some shots should have been in, and others out. I don’t know.

James: It is what it is.

Roger: It changes everyday, so it is what it is.

At some point, you have to be done, I guess.

Roger: Yeah, exactly. At some point you have to say well that’s [it.]

James: That’s very true.

Roger: For us, it was just a great deal of fun doing it, and especially finding a publisher that would work with us. It’s been amazing. It’s been wonderful, because as I say, it’s not my career or job or anything. So to have this sort of book of photography that’s my sketchbook out there is kind of nice.